He founded Flipkart, an online marketplace, with $8,000 in 2007. When it lists later this year, India’s answer to Amazon is likely to be valued at $15 billion. That is because Indians are learning to leapfrog, says Mr Bansal. Many will never see a supermarket, but will go straight from shopping in local kirana (neighbourhood) shops to ordering online. He expects his firm, eventually, to create jobs for 2m.

He is speaking at a dinner in Bangalore, where other guests make similar claims. Some 900m Indians have access to mobile phones. Smartphone use is likely to go up from around 200m now to 500m by 2020. Bhavish Aggarwal, who founded OlaCabs in 2011, says his smartphone-based taxi service has 150,000 drivers, mostly first-time entrepreneurs. It is several times bigger than the Indian branch of Uber. He believes that many Indians, like himself, will skip over having a car of their own.

Advertisers are also leapfrogging. Naveen Tewari and Abhay Singhal are two founders of InMobi, an online firm that serves ads to billions of people globally and is growing fast. They say India, and especially Bangalore, is learning how to succeed with digital startups. It has plenty of engineers, youngsters good at programming, creative types and centres of excellence in the shape of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs). Places like Bangalore are already IT hubs: in Karnataka, the surrounding state, perhaps 1m work in the industry.

Mr Tewari is excited by a new generation of tech businesses, many of them smartphone-based, launched by youngsters who have been through the IITs. He has invested in 19 such startups. Bangalore also benefits from close ties, through the Indian diaspora, to California’s Bay Area.

If business can thrive like this in India, why not government? Nandan Nilekani, the host of the dinner, is all in favour. He co-founded Infosys, a big IT firm, and now wants technology to deliver more public and social gains. For example, he is working on a project called “Ekstep” to spread literacy and numeracy in schools and beyond, using games on smartphones.

Karnataka’s government wants residents eventually to interact by smartphone with hundreds of services from its 60 departments. In December it launched Mobile One, a phone application, for checking property records, birth certificates, car-registration documents and more. The state also runs intercity bus services, utilities and other services, so residents can now book tickets and pay electricity bills or taxes on the phone, or check in with doctors or dentists.

Residents are also encouraged to report local problems through the app. If you spot a pothole or a pile of rubbish in Bangalore, you can alert city officials by uploading a geo-tagged photograph. (Lahore, in Pakistan, has a similar service to get standing water removed, to discourage mosquitoes and dengue.)

Official enthusiasm for online transactions is growing fast. Mr Modi, who turned techno-obsessive when he travelled among the Indian diaspora in America, now uses electronic tablets, not paper, in cabinet meetings. “Digital India is a big programme,” he says. He launched MyGov.in, a national scheme to crowdsource policy ideas from the public. He is convinced government in Gujarat became less corrupt when land records were put online and bids for official tenders went digital and thus more transparent.

“He is driven, he has tasted blood by using technology in so many ways in government,” says an official. In last year’s general election he used holograms to address several rallies simultaneously. A national fibre-optic network is meant to reach all 600,000 villages and their schools by 2017, though that deadline is likely to be missed.

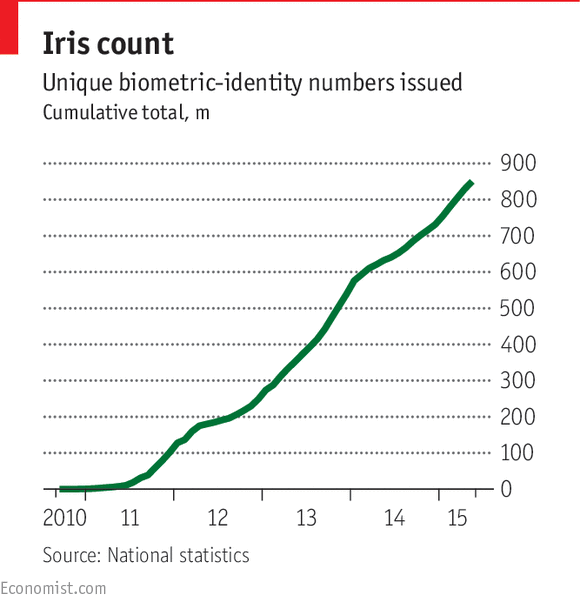

Last July Mr Modi decided to support Aadhaar, a unique identity system launched and run by Mr Nilekani for the previous government. The world’s biggest biometric database has so far created a reliable digital identity for 850m people (see chart). The target is to hit 1 billion this summer.

This framework will support many official applications, which are beginning to be launched. Jharkhand, a small northern state, is using it to deal with an old problem: skiving bureaucrats. State employees now check in and out by having their irises scanned. Their attendance is plotted, live, on a website. Ram Sewak Sharma, who set up the scheme, says habitual offenders are easy to identify and attendance is up. He oversees all technology projects for national government and has introduced the system for the 121,000 national civil servants in Delhi, too. Eventually it could cover all state employees in India, a total of some 18m people.

Here’s looking at you

Back in Jharkhand the unique identity number is also used for monitoring distribution of subsidised food rations. A website lists every recipient, how much food each person has got in each transaction and from which supplier. This makes it harder for suppliers or ration shops to steal, which is how an estimated 40% of the supplies used to disappear. Such monitoring could cut waste dramatically.